Eurovision

Eurovision: Photography project provides ‘therapy’ for Ukrainian refugees

3 years ago

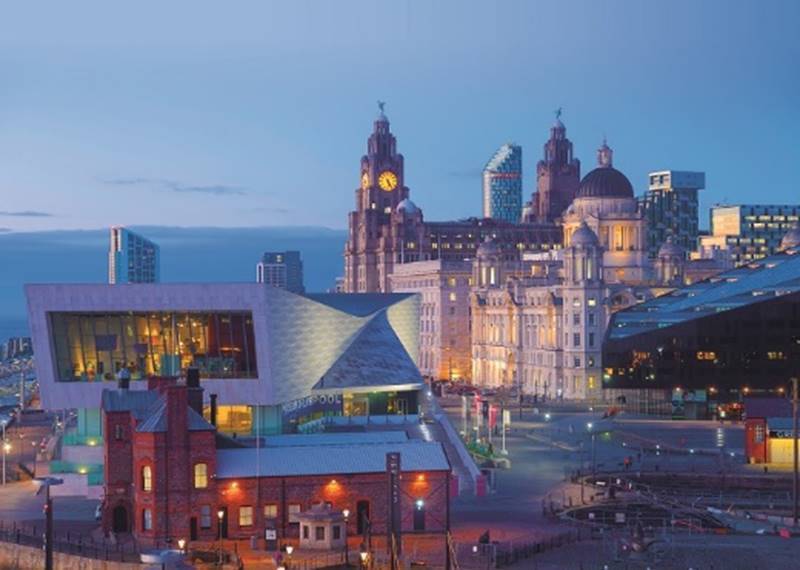

The photography exhibition is on display in Liverpool while the city hosts the Eurovision Song Contest in place of last year’s winner, Ukraine.

An exhibition showing 24 portraits of Ukrainian women who fled the war and resettled in Liverpool has gone on display in the city during the Eurovision Song Contest, and was described as being like a “form of therapy” for those photographed.

Photographer Ean Flanders, 58, said that he was inspired to undertake the project after meeting two Ukrainian women who were living with his friends after being forced to flee their country.

The portraits, showing the Ukrainian women standing or sitting against a dark grey studio background, are on display at Baltic Creative in Liverpool and are accompanied by testimonies written by the women in Ukrainian and translated into English.

From being awoken in the early hours by a panicked phone call informing them of the invasion, to grappling with pregnancy and separating from their husbands in the months after arriving in the UK, the testimonies tell the women’s heart-breaking and inspiring stories.

Mr Flanders said he wanted the portraits to give the general public in Liverpool “more of an in-depth understanding” of the hardship faced by the female Ukrainian refugees living in the city, as well as showcase the women’s strength.

The Liverpool-based professional photographer, originally from London, said: “All these women are going through some form of trauma due to the war, due to not being with their families, due to not being able to speak English, so I just wanted to show their feelings, their emotions, their anger.”

He added: “Not all of us have contact with Ukrainians who are in the city so I thought having this exhibition with these women’s portraits on the wall would give an opportunity for some of these women’s experiences to be shared.”

Among the subjects of the exhibition is Olena Malenk, 37, who fled Kyiv with her two sons Platon, seven, and Lev, five, after seeing military aircraft soar over the capital and drop missiles on her city.

Forced to flee without her husband, Gregory, as most men of fighting age are not permitted to leave the country, Ms Malenk discovered upon arrival in Liverpool that she was pregnant with twins.

Wearing a long black dress and standing against a grey studio background, Ms Malenk’s photograph shows the mother looking down as she holds her bump.

The photoshoot allowed her to recognise her “power and confidence” as a pregnant woman who has sought to protect her children from war and create a new life, according to a testimony she composed for the exhibition.

Mr Flanders was inspired to undertake the project by Ukrainian women, Olha Kruglova, 40, and Anastasiya Sydorenko, 33, who were being hosted by his friends in Liverpool and who he ultimately collaborated with to bring the exhibition to life.

“They were telling me about the difficulties they had in adjusting and adapting to UK life and the Liverpool accent,” Mr Flanders said, which prompted him to take their photographs and find more Ukrainian women for an exhibition.

Ms Sydorenko was informed that Russia had invaded her country by the trembling voice of her sister, Nastya, over the phone at around 5am on February 24 2022, and several minutes later she heard the wail of an air alert siren.

Ms Sydorenko, her husband and their daughter stayed in the basement of her father’s home for 10 days, until missiles fell on the neighbourhood and made the walls of the house shake as their daughter slept on a sack of potatoes.

“She didn’t deserve such a childhood, to hear these sounds, to fear, to cry, to wake up at night and run to hide not understanding what was going on,” Ms Sydorenko wrote in her testimony.

After arriving in Liverpool, Ms Sydorenko learned that her husband had left her and she fell into a “deep depression” for a period, before slowly pulling herself out of the depths of despair.

She wrote: “I am proud of myself that I didn’t give up and I didn’t let this situation take over me. Everything that was meant to destroy me became my power.”

An unexpected outcome of the project was that it felt like a “form of therapy” for the women photographed, as it allowed them the opportunity to discuss their experience, Mr Flanders said.

He said: “I didn’t think about it at the time, but many of the women have told me that taking part in this project is one of the best things that they’ve done because it’s allowed them to look at themselves and talk about their experiences openly, and to feel some sort of self-worth and strength.

“There’s so many things that I didn’t think the project would bring out.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us