Culture

Campaign for permanent memorial in Liverpool to enslaved people who died and were buried in the city

6 years ago

A campaign has been launched to erect a memorial in Liverpool to enslaved people who died and were buried in the city.

Laurence Westgaph, the historian and slavery tour guide behind the fund-raising, believes the powerful energy of the Black Lives Matter protests should be channeled to create a lasting reminder of those who lost their lives in slavery.

And, after the controversial toppling of the Edward Colston statue in Bristol, he says a putting up a monument would be a better way to have a more balanced conversation than pulling down the statues of slave traders.

“Instead of using all this positivity to focus on tearing stuff down, why doesn’t everyone who has a serious interest in Liverpool and slavery join those of us who have been campaigning for decades to have a fitting memorial erected to the victims of the slave trade?” he says.

“Once you start tearing things down then straight away the people who think they should stay up are going to be repulsed by that and not want to know.

“If you’re somebody who respects history and you want those memorials to remain because they are part of the city’s history, then why would you oppose something that tells the other, equally important side of that?

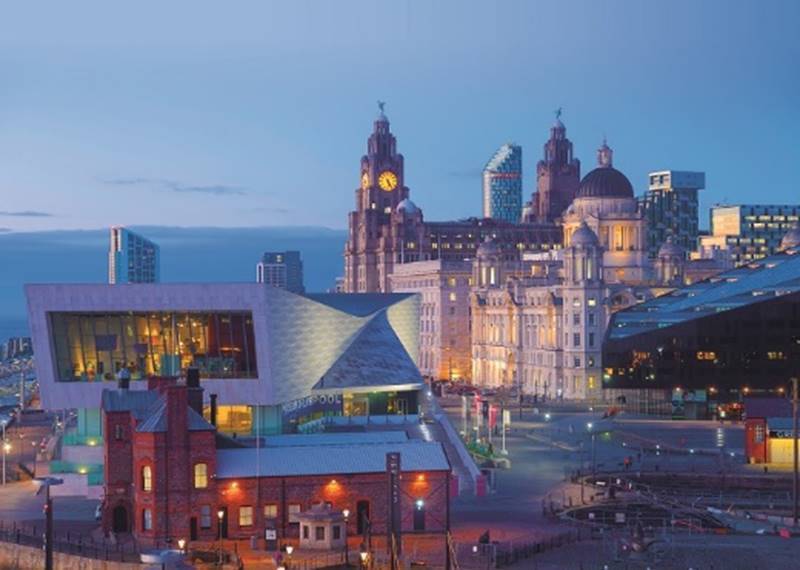

International Slavery Museum

“I’m very much in favour of telling a complete story, that doesn’t mean leaving those statues up without interpretation – I do that every time I do a tour – but it also means you get a far more nuanced history of the great and the good.”

Laurence has been personally raising funds to specifically commemorate the enslaved people who lived, died and are actually buried here. He has now launched a public fund-raiser, The Liverpool Enslaved, which he hopes will make the memorial a reality as soon as possible.

“Successive historians have said that no enslaved people came to Liverpool but I’ve researched this in depth, gone through all the parish records, and I’ve found lots. With some, their masters obviously liked them so you see obituaries to ‘a faithful black servant’, but everyone wasn’t treated well, and everyone wasn’t treated badly.

Laurence Westgaph

“Enslaved people ran away, Liverpool newspapers were full of adverts for runaways, and others were left annuities in wills or given their freedom in wills, so it’s a far more nuanced story than you might think.

“For me, the public realm is the perfect classroom to tell these stories of individuals. I disagree that this should just be taught in schools, so many people turn off when you put a book in front of them or lecture them – so many young people come on my tours and I couldn’t engage with them the same way in a classroom that I can if I take them out and show them the monuments and buildings.

“You can choose not to go to a museum but those statues and street signs are something you can’t ignore. People ask me ‘why is it called Bold Street?’ and I tell them it was named after Jonas Bold who was a slave trader. That’s how you start the conversation.

“You can choose not to go to a museum but those statues and street signs are something you can’t ignore. People ask me ‘why is it called Bold Street?’ and I tell them it was named after Jonas Bold who was a slave trader. That’s how you start the conversation.

“When I go to Gladstone’s statue I explain that he was obviously four times Prime Minister, born in Liverpool, but his family were involved in the slave trade. He’s seen as this great humanitarian but if you do more research you find out that all of his earliest speeches in the Houses of Parliament were in defence of slavery.”

Laurence believes that instead of trying to erase evidence of the city’s history, current council leaders should try to redress the balance.

“So if there’s a new building or a new thoroughfare, I think the council should consider naming it after someone who was involved in doing away with the slave trade. That’s how you right the wrongs of the fact that these streets are named after the men who made their money from the enslavement of Africans, not by wiping them away.”

Laurence launched the fund-raiser through Facebook and has already exceeded his first £10,000 target.

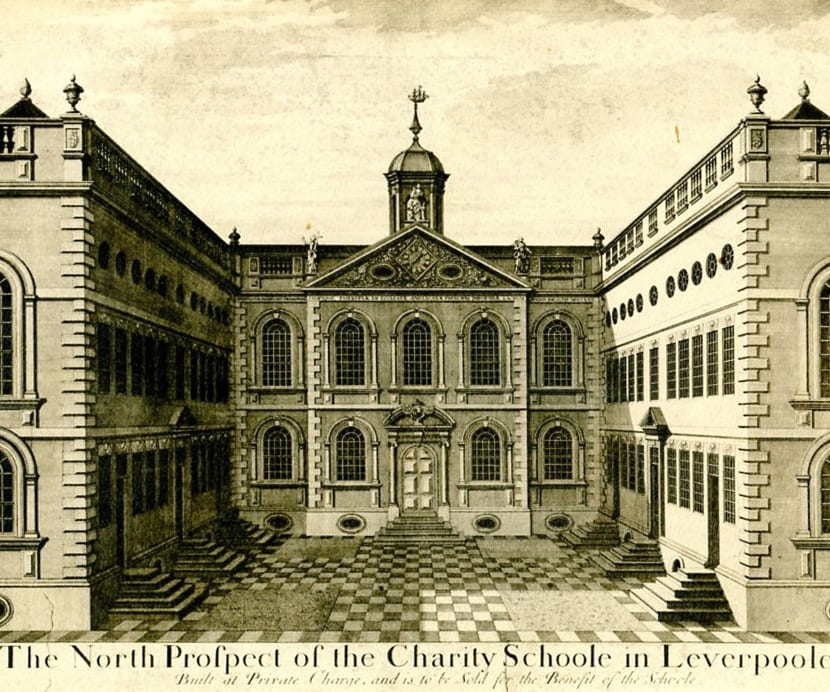

“Many of these forgotten individuals have laid in unmarked graves for over 200 years,” he explains. “Many were not only interred without a marker but even without their names. For example, on 23 Sept 1778 “A Black boy belonging to Captain Penny” was buried at what is now St John’s Gardens.

“Although we do not know many of their names, these individuals deserve to be respectfully commemorated.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us