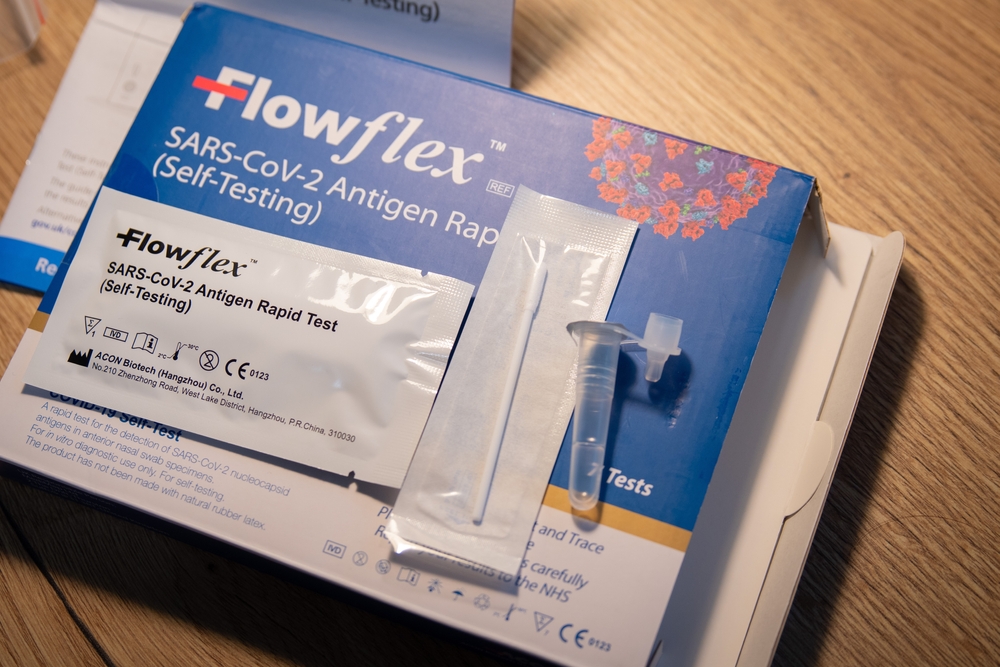

Coronavirus

Everything you need to know about the Oxford Covid-19 vaccine

5 years ago

The AstraZeneca/Oxford University vaccine – called ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 – uses a harmless, weakened version of a common virus which causes a cold in chimpanzees.

The AstraZeneca/Oxford University vaccine has become the latest coronavirus jab approved for use in the UK.

How does the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine work?

The vaccine – called ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 – uses a harmless, weakened version of a common virus which causes a cold in chimpanzees.

Researchers have already used this technology to produce vaccines against a number of pathogens including flu, Zika and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers).

The virus is genetically modified so that it is impossible for it to grow in humans.

Scientists have transferred the genetic instructions for coronavirus’s specific “spike protein” – which it needs to invade cells – to the vaccine.

When the vaccine enters cells inside the body, it uses this genetic code to produce the surface spike protein of the coronavirus.

This induces an immune response, priming the immune system to attack coronavirus if it infects the body.

Phase 3 trial data showed the jab was 70.4% effective on average across two different dose regimes and possibly up to 90% when one half dose is given followed by a further full dose.

What dosing regime has the regulator recommended?

The MHRA has recommended over 18s should receive two doses to be administered with an interval of between four and 12 weeks.

Does it differ from Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccine?

Yes. The jabs from Pfizer and Moderna are messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines.

Conventional vaccines are produced using weakened forms of the virus, but mRNAs use only the virus’s genetic code.

An mRNA vaccine is injected into the body where it enters cells and tells them to create antigens.

These antigens are recognised by the immune system and prepare it to fight coronavirus.

No actual virus is needed to create an mRNA vaccine. This means the rate at which the vaccine can be produced is accelerated.

What about antibodies and T-cells?

The Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Moderna vaccines have been shown to provoke both an antibody and T-cell response.

Antibodies are proteins that bind to the body’s foreign invaders and tell the immune system it needs to take action.

T-cells are a type of white blood cell which hunt down infected cells in the body and destroy them.

Nearly all effective vaccines induce both an antibody and a T-cell response.

A study on the AstraZeneca vaccine found that levels of T-cells peaked 14 days after vaccination, while antibody levels peaked after 28 days.

Can the Oxford vaccine be manufactured to scale?

Yes. The UK Government has secured 100 million doses of the Oxford University and AstraZeneca vaccine as part of its contract, enough for most of the population.

The head of the UK Vaccine Taskforce, Kate Bingham, has said she is confident it can be produced at scale and AstraZeneca said it aims to provide millions of doses to the UK in the first quarter of 2021.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said rollout would begin on January 4.

Can this vaccine help the elderly?

There have been concerns that a Covid-19 vaccine will not work as well on elderly people, much like the annual flu jab.

Earlier data from the Oxford University and AstraZeneca vaccine trial suggests that there has been “similar” immune responses among younger and older adults, with Moderna reporting the same.

In a statement earlier this year on its phase two data, Oxford University said its data marked a “key milestone”, with the vaccine inducing strong immune responses in all adult groups.

How has this come about so quickly?

The timetable for developing and approving a Covid vaccine has been condensed due to the coronavirus crisis.

What is the usual process for developing a vaccine?

Traditionally vaccine development takes several years and includes various processes, including design and development stages followed by clinical trials – which in themselves need approval before they even begin.

The trials take place in three sequential stages – also known as phases. The research will show whether a vaccine generates antibodies but also protects people from disease. They will also identify any safety issues.

Once the trials are complete, the information gathered by researchers is sent to regulators for review.

This is thoroughly analysed by clinicians and scientists before being approved for widespread use.

Then, after approval from regulators, people can start to receive the vaccine.

Is this different because of the pandemic?

The process looks slightly different in the trials for a Covid vaccine.

While the early design and development stages look similar, the clinical trial phases have overlapped – instead of taking place sequentially.

But won’t that mean that safety is compromised?

Even though some phases of the clinical trial process have run in parallel rather than one after another, the safety checks have still been the same as they would for any new medicine.

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has adopted the phrase “safety is our watchword”.

Regulators have said they will “rigorously assess” the data and evidence submitted on the vaccine’s safety, quality and effectiveness.

And, in most clinical trials, any safety issues are usually identified in the first two to three months – a period which has already lapsed for most vaccine frontrunners.

What does ‘approved for use’ mean?

For a medicine to be used in the UK it has to be granted a licence. This means that it has been through all the rigorous safety and efficacy checks and regulators are confident in the findings of the clinical trials.

By reviewing the data as they become available, the MHRA can reach its opinion sooner on whether or not the medicine or vaccine should be licensed without compromising the thoroughness of their review.

How will a vaccine be rolled out?

There is considerably less uncertainty over the rollout of the Oxford vaccine, with the scene having largely been set earlier in December with the Pfizer/BioNtech jab.

The Oxford vaccine can be stored at fridge temperature for at least six months so it is hoped the logistics of administering it will be easier.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock said the approval was “fantastic news” and confirmed that the roll out would begin on January 4.

AstraZeneca said was building up a manufacturing capacity of up to 3 billion doses worldwide next year, and aims to supply the UK with millions of doses in the first quarter in 2021.

Now there are more vaccines, does this mean a wider range of people can be vaccinated?

All of the people at the top of the priority list created by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) have not yet been vaccinated.

Therefore vaccinators will continue to work their way through the list.

It is hoped more people in care homes will be reached with the rollout of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine.

The JCVI’s guidance says the order of priority should be:

1. Older adults in a care home and care home workers

2. All those who are 80 years of age and over and health and social care workers

3. All those who are 75 years of age and over

4. All those who are 70 years of age and over and clinically extremely vulnerable individuals, excluding pregnant women and those under 18 years of age

5. All those who are 65 years of age and over

6. Individuals aged 16 to 64 years with underlying health conditions

7. All those aged 60 and over

8. All those aged 55 and over

9. All those aged 50 and over

Aren’t there other vaccines?

Yes. As well as the Pfizer vaccine which has an efficacy of 95%, a number of other jabs the UK has secured doses of.

Oxford data indicates the vaccine has 62.1% efficacy when one full dose is given followed by another full dose, but when people were given a half dose followed by a full dose at least a month later, its efficacy rose to 90%.

The combined analysis from both dosing regimes resulted in an average efficacy of 70.4%.

Final results from the trials of Moderna’s vaccine suggest it has 94.1% efficacy, and 100% efficacy against severe Covid-19.

Which jab is best?

The early contenders all have high efficacy rates, but researchers say it is difficult to make direct comparisons because it is not yet known exactly what everyone is measuring in the trials.

How many doses has the UK secured?

The UK has secured access to 100 million doses of the AstraZeneca/Oxford University vaccine, which is almost enough for most of the population.

It also belatedly struck a deal for seven million doses of the jab on offer from Moderna in the US.

The deals cover four different classes: adenoviral vaccines, mRNA vaccines, inactivated whole virus vaccines and protein adjuvant vaccines.

The UK has secured access to:

– 100 million doses of the Oxford vaccine

– 60 million doses of the Novavax vaccine

– Some 30 million doses from Janssen

– 40 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine – the first agreement the firms signed with any government

– 60 million doses of a vaccine being developed by Valneva

– 60 million doses of protein adjuvant vaccine from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Sanofi Pasteur

– Seven million doses of the jab on offer from Moderna in the US.

What do they cost?

Pfizer/BioNTech is making its vaccine available not-for-profit.

According to reports, the Moderna vaccine could cost about 38 dollars (£28) per dose and the Pfizer candidate could cost around 20 dollars (£15).

Researchers suggest the Oxford vaccine could be relatively cheap to produce, with some reports indicating it could be about £3 per dose.

AstraZeneca said it will not sell it for a profit, so it can be available to all countries.

However, the details of the deals made by the UK Government have not been made public.

How do we know the vaccines are safe?

Researchers reported their trials do not suggest any significant safety concerns.

Will people get a choice about which vaccine they are given?

As things stand the vaccines will be rolled out as and when they become available.

No announcement has been made on whether one might be given priority over another as they become ready on a mass scale.

People are not expected to be able to choose which jab they want to receive.

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us