History

A look back at the history of Liverpool’s Royal Albert Dock

2 years ago

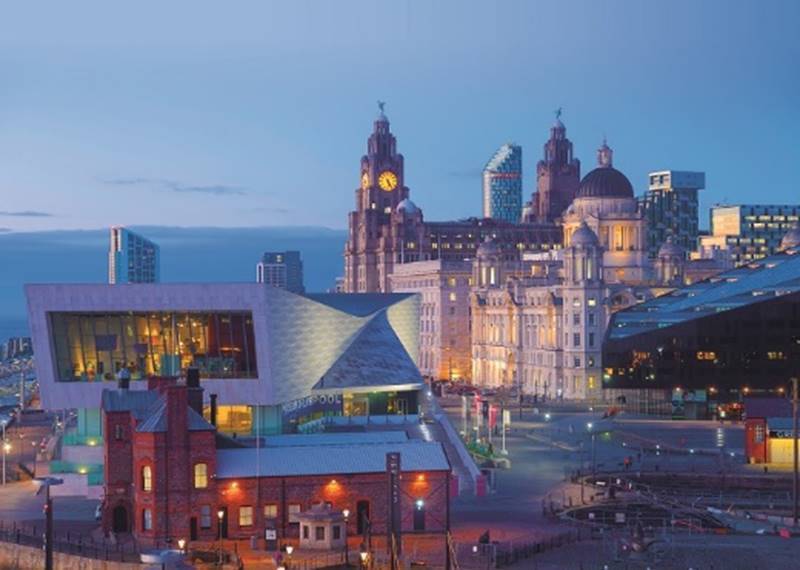

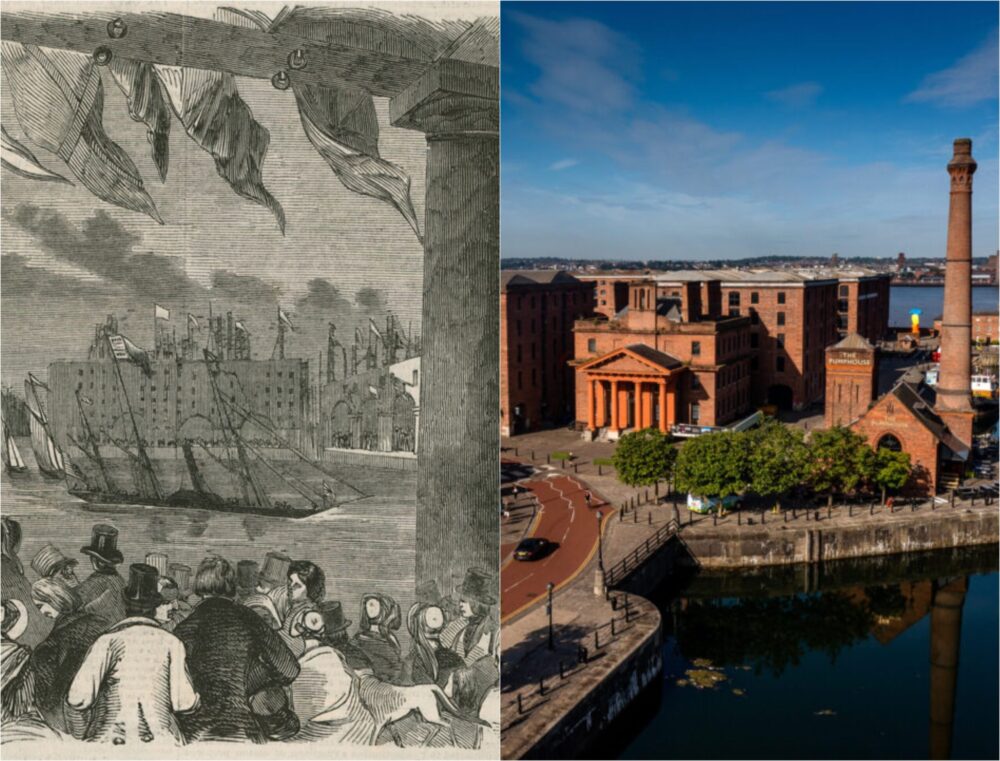

The Royal Albert Dock in Liverpool stands as a symbol of the city’s maritime legacy, showcasing its journey from a thriving port to a vibrant cultural and tourist destination.

This detailed history traces the evolution of Royal Albert Dock, highlighting its periods of decline, and subsequent renaissance.

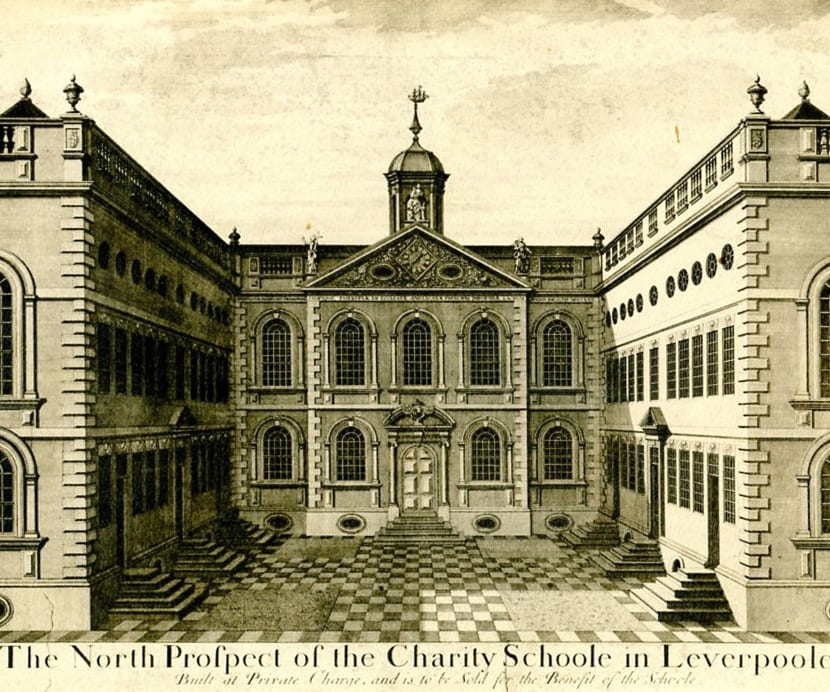

Before the early 18th century, Liverpool had no docks. Ships anchored in the River Mersey or in the tidal inlet known as the ‘pool,’ and cargo was brought ashore by small boats.

Recognising the need for a proper docking system, dock engineer Thomas Steers initiated the construction of an embankment across the south of the pool in 1710, creating Britain’s first commercial wet dock, known as the Old Dock.

This groundbreaking development opened for shipping in 1715, marking the beginning of Liverpool’s transformation into a major port city.

The Old Dock quickly became insufficient for the rapidly growing maritime activities. In 1753, the South Dock was completed, later renamed Salthouse Dock due to its proximity to John Blackburne’s saltworks. By 1765, three graving docks were built, forming the Canning Graving Docks and the Canning Half-Tide Basin.

Despite proposals for constructing warehouses around the docks in 1810 and 1820, these ideas were initially rejected due to opposition from local warehouse owners who enjoyed a storage monopoly.

However, the need for more efficient dock operations persisted.

The Old Dock eventually became too small and was filled in by 1826, with the Customs House built on its site. In 1839, dock engineer Jesse Hartley proposed an enclosed dock warehouse system inspired by London’s St. Katherine’s Dock. His vision aimed to streamline cargo handling by allowing goods to be unloaded directly from ships into warehouses, reducing turnaround times.

Construction of the Albert Dock began following the passage of the Dock Act in 1841.

Hartley’s innovative use of non-combustible materials, including brick, stone, and cast iron, was a significant advancement in dock design. In 1846, HRH Prince Albert officially opened the dock, and by 1848, the Albert Dock complex was fully completed.

The Albert Dock was revolutionary, featuring the world’s first hydraulic warehouse machinery. The five-storey warehouses were constructed using over 23 million bricks, and the iconic cast iron columns, measuring four feet in diameter and 25 feet high, supported the structure. The dock system included hydraulic cranes, hoists, and lifts, powered by a hydraulic pumping station built in the 1870s.

The warehouses were designed to be fireproof, using methods first employed in textile mills. Only non-combustible materials were used, and the floors were made of tile or brick, with the curved roof constructed from galvanized wrought iron. This design not only ensured safety but also facilitated efficient cargo handling.

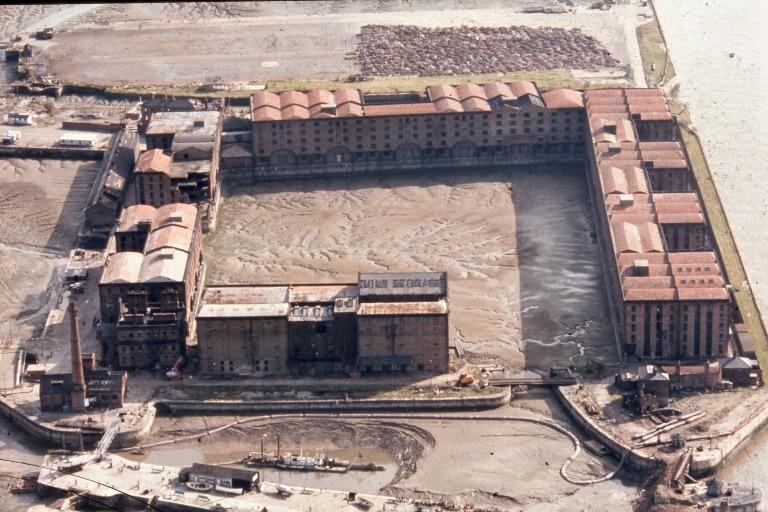

By the mid-20th century, the advent of larger ships and new cargo handling technologies rendered the Albert Dock’s facilities obsolete.

The decline began in 1945, and by 1971, the entire South Docks complex, including the Albert Dock, was shuttered and silenced. Containerisation shifted the city’s dock focus north towards Seaforth, leaving the pioneering Albert Dock in need of a new purpose.

In 1952, the Albert Dock was awarded Grade I listed status, becoming the largest collection of Grade I listed buildings in the UK.

The revival of Albert Dock began in the 1980s. In 1981, the Merseyside Development Corporation (MDC) was established to regenerate Liverpool’s waterfront. The Arrowcroft Group put forward an ambitious vision to develop the abandoned complex for commercial, leisure, and residential uses. By 1984, water returned to the Albert Dock, and the Cutty Sark Tall Ships Race was hosted.

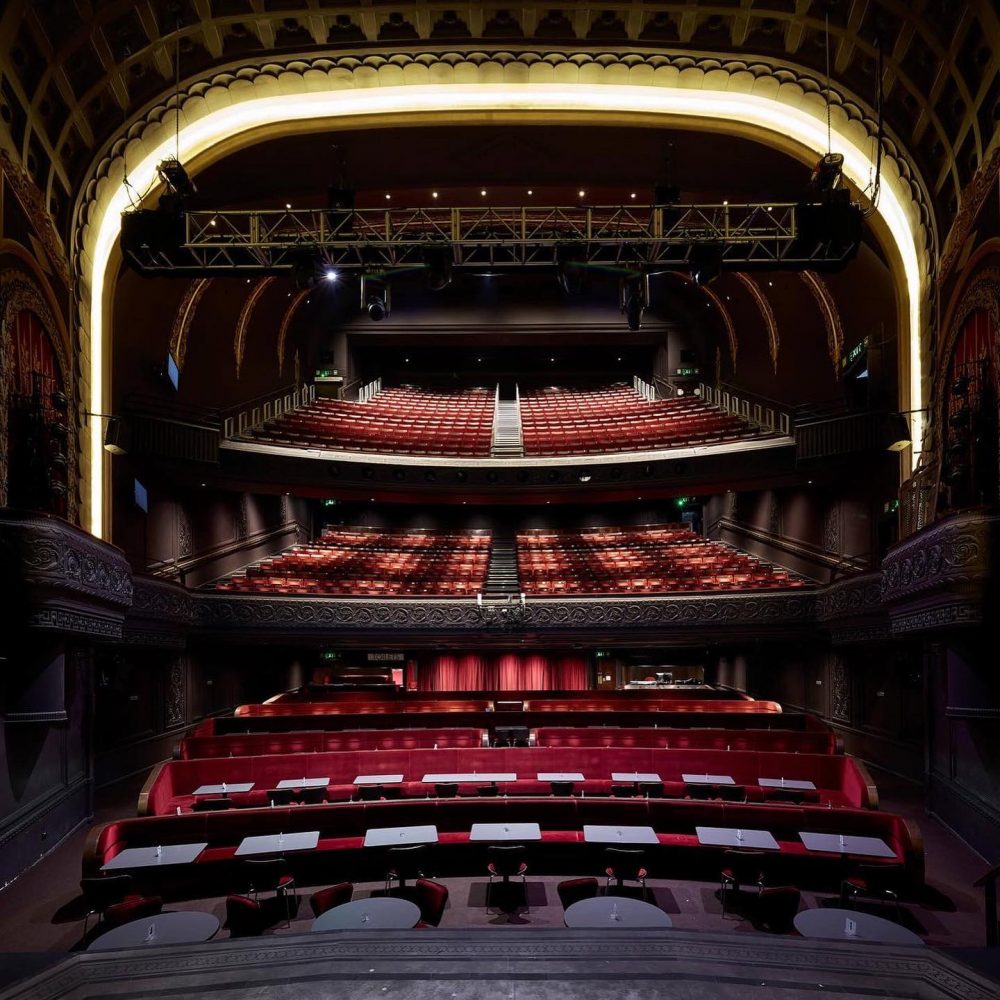

The opening of the Merseyside Maritime Museum in 1986 marked the beginning of Albert Dock’s renaissance. The fully refurbished dock was reopened by HRH the Prince of Wales in 1988, coinciding with the opening of Tate Liverpool.

The Dock’s distinctive columns were broadcast into homes across the country by the groundbreaking ITV show, This Morning, which premiered in 1988.

In 2004, the Dock became a centrepiece of Liverpool’s UNESCO World Heritage status, recognised for its historical significance as a maritime city. The Dock played a pivotal role in Liverpool’s development as a major trading center during the British Empire.

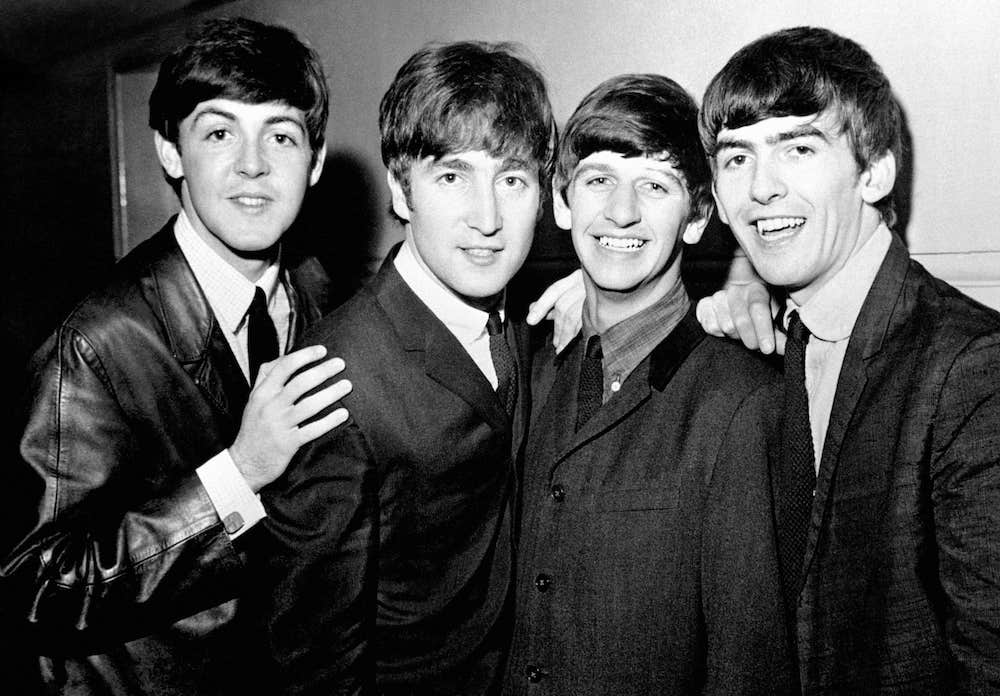

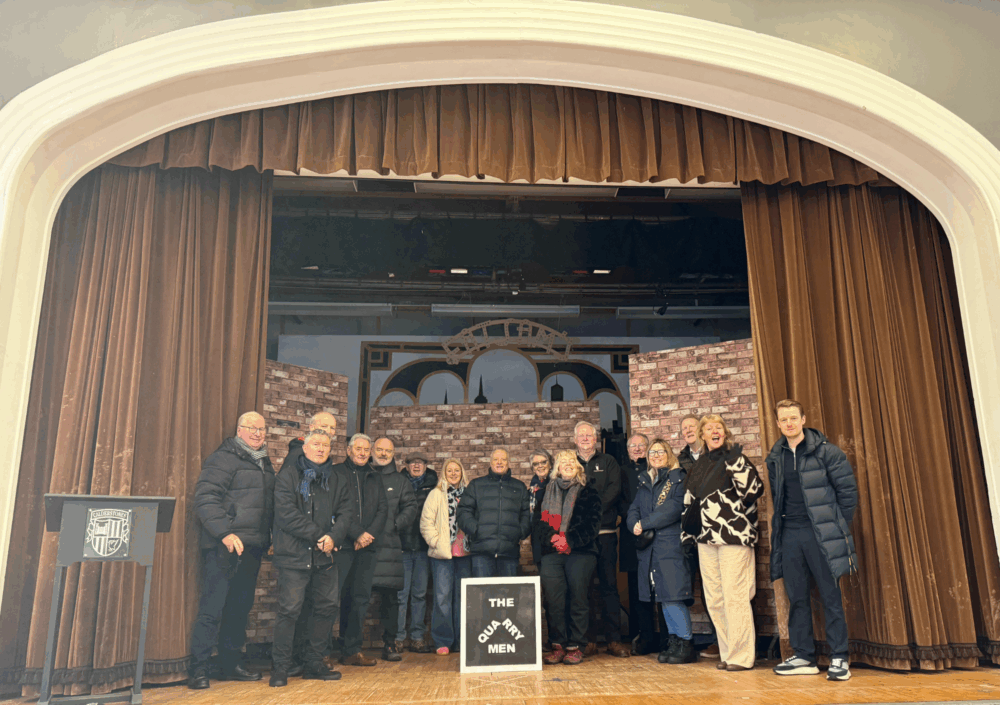

Today, the Albert Dock houses cultural giants like the Maritime Museum, The Beatles Story, and the Tate Liverpool. It attracts millions of visitors annually, making it the North West’s most visited free tourist attraction.

The Dock’s transformation has included investments in public spaces, free Wi-Fi, and a vibrant seasonal events program.

In 2018, the Dock was granted Royal status in recognition of its pivotal role in Liverpool’s fortunes. As it approaches its 175th anniversary, the Albert Dock continues to be a symbol of Liverpool’s resilience, innovation, and cultural significance.

From its early days as Britain’s first commercial wet dock to its current status as a vibrant cultural hub, the Royal Albert Dock’s history is a testament to Liverpool’s maritime legacy and enduring spirit. Its ability to adapt and reinvent itself over the centuries serves as a powerful reminder of the city’s rich heritage and bright future.

The Dock is set for another transformation as the National Museums Liverpool’s Waterfront Transformation Project has now secured planning permission, which aims to revitalise the Canning Quaysides and Dry Docks into a space for education, contemplation and recreation.

At the heart of this £15 million redevelopment lies the restoration of the south dry dock, constructed in 1765, to make it accessible to the public for the first time.

Thanks to a £10 million contribution from the Government’s ‘Levelling Up’ fund, plans include the construction of a new stop wall, a staircase, and a lift, enabling visitors to explore this historic site.

Plans also feature a twin-lever footbridge from the Royal Albert Dock across to the Canning quayside. The wider public realm will be enhanced with level pathways, an open-air events space, and significant improvements to the interpretation of items around the site. You can find out more about this here.

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us