Liverpool News

Ahead of St Patrick’s Day: Find out why Liverpool is known as the second capital of Ireland

2 years ago

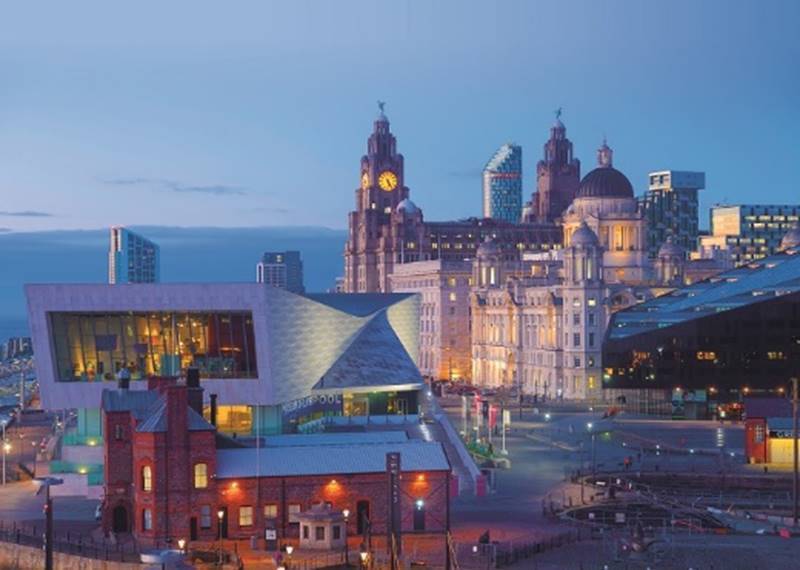

It’s that time of the year again as St Patrick’s Day arrives on March 17, and when it comes to celebrating this special day, Liverpool knows how to do it.

With bars bursting at the seams and a celebratory parade through the city streets, it’s easy to see why St Patrick’s Day in Liverpool is one of the highlights of our calendar.

Irish culture runs deep within its DNA, and you’ll never have to go far to find someone with a strong connection to the Emerald isle. But what’s the reason for the links which have led to the city being named the second capital of Ireland?

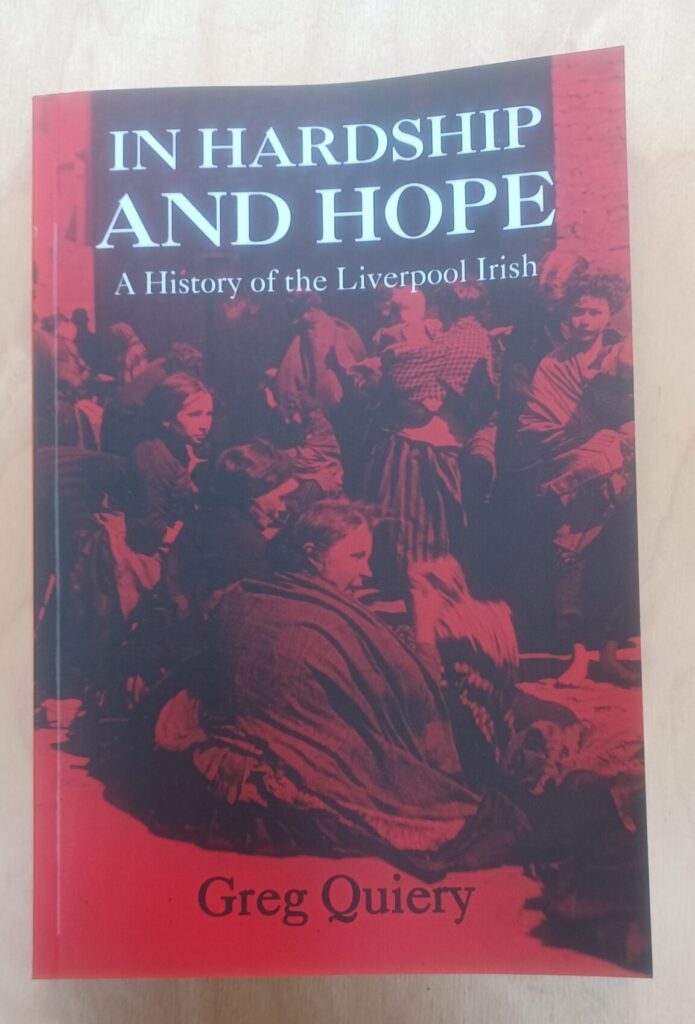

Belfast-born author and historian Greg Quiery agrees many people believe it began with the migration of Irish people to Liverpool during the time of Great Famine between 1847 to `1851.

But in truth it began decades before.

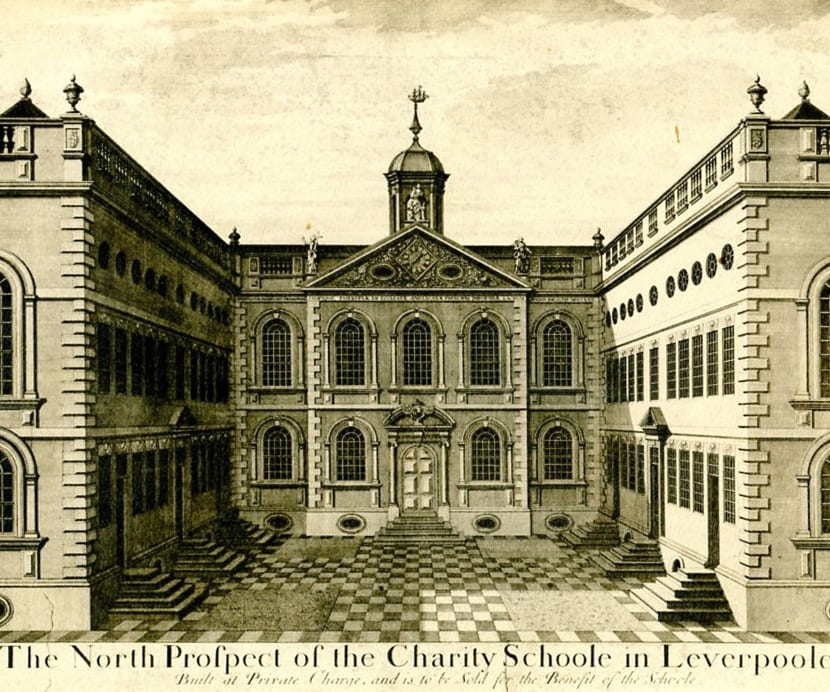

Greg, author of In Hardship and Hope: A History of the Liverpool Irish, says: “There were a lot of Irish people in Liverpool before the 1840s, with the former school in Pleasant Street – still standing to this very day – having been built by the Benevolent Society of St Patrick (founded in 1807) for the children of Irish families a testament to that.”

The connection goes back to 1800 when both the Irish and Great Britain Parliaments passed the Acts of Union which abolished Irish legislature and merged the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

He explains: “Ireland was basically told you’ll lose your parliament, but you’ll gain from being part of the United Kingdom. But in fact, Irish industry collapsed and loads of skilled and unskilled workers came over to Britain, and Liverpool was the nearest city.

“There was lots of work here, and so it attracted people even then.”

The famine did reinforce the numbers.

“There was a huge influx as a result of the famine, with around 1.5 million people coming to the Port of Liverpool, about a third of them coming on normal business, and another third going on to other parts of the world.

“A large number of them were absolutely poverty-stricken, and they stayed in Liverpool.

“A census around the time shows that the percentage of Irish-born in Liverpool peaked around the 1850s at about 22% of the population!

“Succeeding generations married and had families, multiplying the number of Liverpudlians with an Irish connection.”

Liverpool was attractive not just because of its proximity to Ireland, but because it was a seaport: “Life was casual and unpredictable for many,” Greg goes on.

“It contrasted to life in Manchester, for example, where people were working in mills and started and finished at a certain time every day, they knew a year in advance when their holidays would be, they knew what their wages would be, and it was a very regular and organised way of life. You were on the stopwatch.

“In Liverpool so many people were working casually on the docks or going to sea. Dockers were hired for a day or a half day. Pay was poor. You could turn up if you wanted to work, and if you didn’t feel like getting up, you didn’t. If there wasn’t work, you went home.

“People would jump on a ship at short notice and be away for six months, and they would travel to South America, North America, Asia, and that was Liverpool in the 19th Century. It was a very distinctive place!

“Migration is about push and pull. The push factor was the poverty in Ireland; the pull factor was that Liverpool was one of the most prosperous cities in the world, and jobs could be well-paid especially compared with what you’d get in Ireland.”

Irish communities developed around the city, in Frederick Street where the old docks were and where John Lewis is now, and around Pitt Street, and in the north end around Lace Street and Scotland Road.

He adds: “In the 19th and early 20th Century generally to be Irish was to be Catholic. Irish Protestants also came to Liverpool, but they integrated more easily with similar-sounding surnames like Thompson and Jones, and they got skilled jobs more easily. Catholics were often discriminated against in employment.

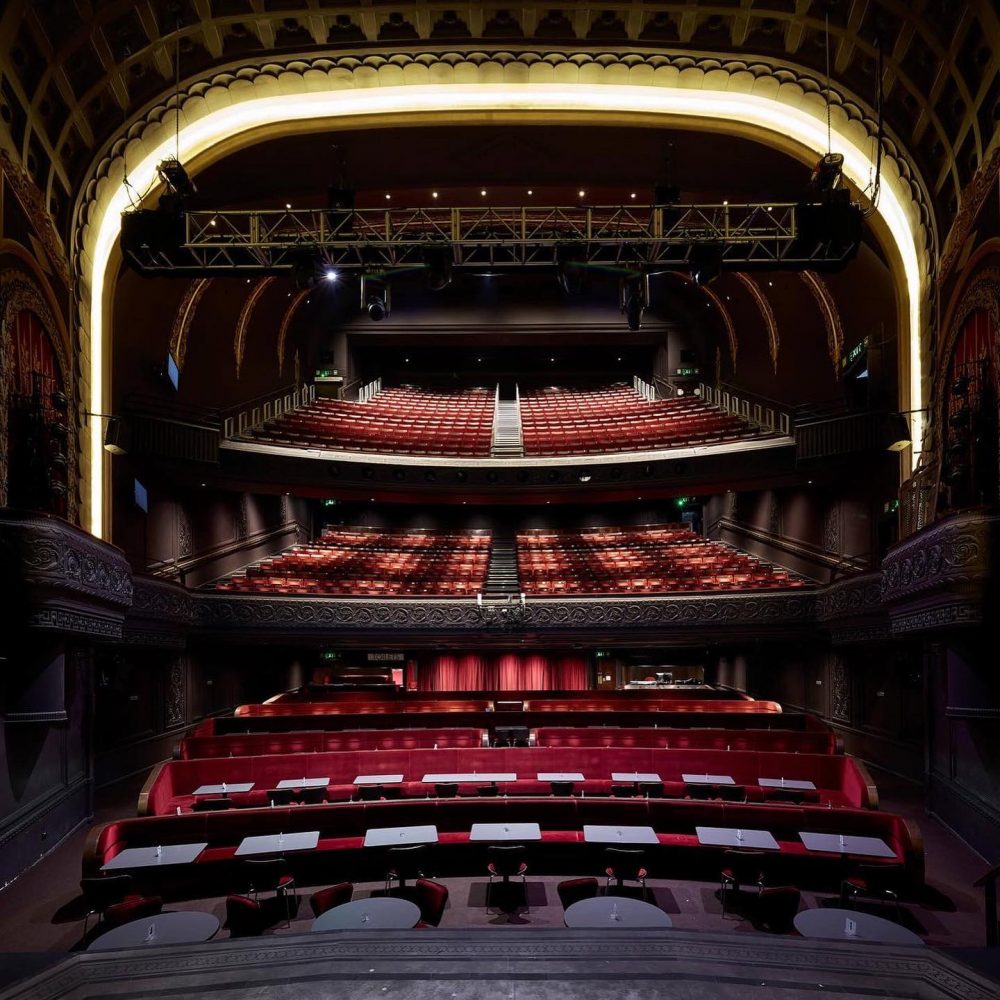

“Irish communities manifested themselves in the Catholic parishes which grew and where people married within the parish even though they were living in such a big city. Each parish would have its own club, society, its own days out, football team, or choir.

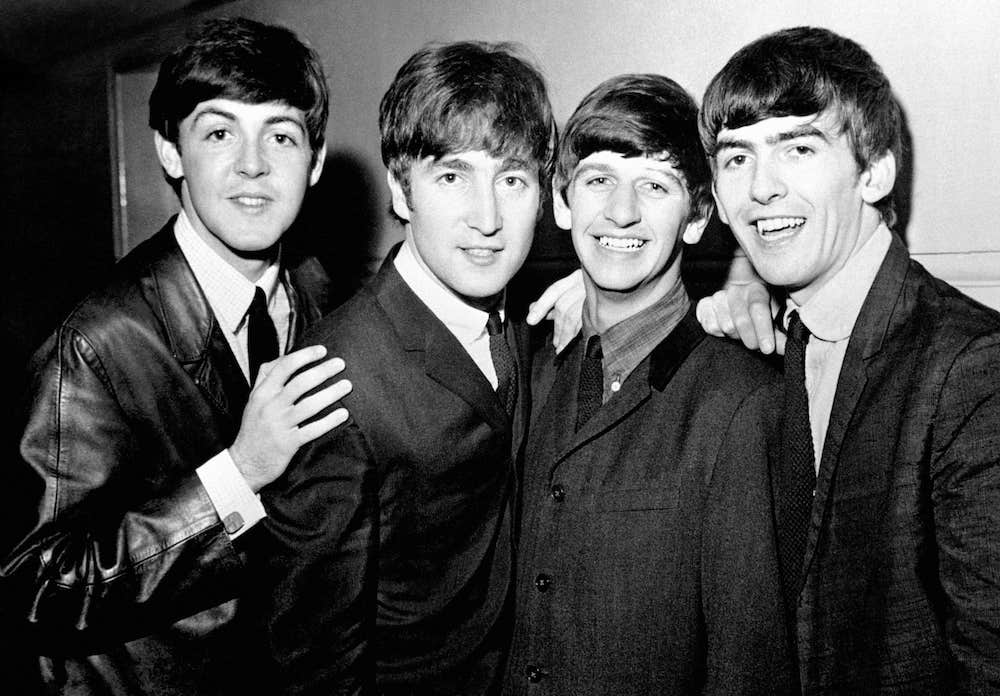

“They got baptised there, married there and they had their funerals there. John Lennon’s great great grandparents got married at St Anthony’s Church on Scotland Road in 1848. They were typical Irish migrants; Paul McCartney’s family had strong Irish connections too.

“Those are just people we know about but who have a typical family history, and the links have persisted because that community thing was very strong.”

Since the Peace Process Irish identity has blossomed, says Greg, and many more people feel able to culturally express that identity.

“There was a fork in the road in the late 1920s when Ireland went its own way and in Liverpool a very distinctive Liverpool culture, heavily influenced by Irish culture, began to develop.

“That scepticism towards authority and attitude to British authority, as well as attitude to music and sport – you have keen interest in horse racing in Ireland and you have the Grand National in Liverpool. Those little parish clubs were where fanaticism about football was nurtured. There are a lot of similarities between Irish culture and what you find in Liverpool today.

“The cultural renaissance in the ‘60s was a big factor. Historically, there was intense sectarianism which led to violence – the nadir of that in 1909 – but in the ‘60s the city put that behind it. You had not just The Beatles, but the other bands, writers and poets, comedians, sports people, and people at that stage began to say ‘I’m not Catholic or a Protestant’, I’m from Liverpool.

“And that’s when people began to identify as Scousers and be proud of that identity.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us