Liverpool News

Liverpool’s Director of Public Health outlines health challenges in the city by 2040 and actions needed to tackle them

2 years ago

Liverpool’s Director of Public Health is calling for radical – and systemic – changes to the way the city responds to health challenges to prevent reduced life expectancy and extended periods of ill health for residents in the city.

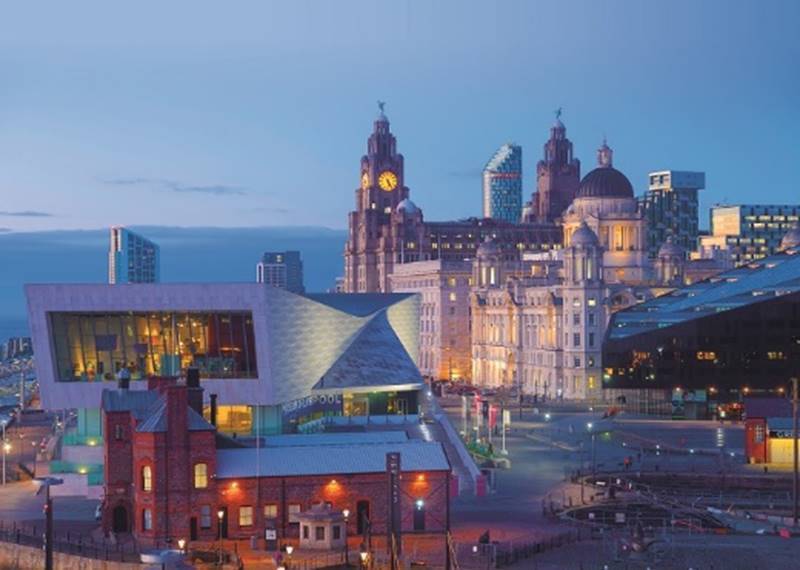

An 80-page document, written by Professor Matt Ashton – ‘State of Health in the City’ – to be discussed at a Council meeting of all Elected Members at Liverpool Town Hall on Wednesday 17 January – looks at the health of Liverpool’s inhabitants since 1984, and outlines the work the Council, its partners and the government need to do to tackle the challenges it is projecting by 2040.

The report says that unless changes are made, the city’s residents could:

• spend more than a quarter of their life (26.1%) in ill health

• life expectancy for women would fall by one year

• the number of adults experiencing depression could more than double over the coming decade

The current position

Liverpool is the third most deprived local authority in England, with 63% of residents living in areas ranked among the most deprived in England, and 3 in 10 children living in poverty.

Residents are living longer than previously, but progress has stalled over the last decade.

Life expectancy is currently 76.1 years for men and 79.9 years for women (national average: 79.4 years for men / 83.1 years for women). However, life expectancy at birth varies widely in the city, and life expectancy varies by 15 years between those in the poorest and most affluent areas, and those in the most deprived areas live 18 more years in poor health.

Projections for 2040

- The life expectancy of women will fall by one year, and they will be in good health for 4.1 fewer years than they are currently. Although they are starting from a lower base, men will live 6 months longer than currently, and more of that time – 1.8 years – will be spent in good health.

- There will be an increase of between 33,000 – 38,000 in the number of people with major illness, defined as at least two long-term conditions such as high blood pressure (up 20,300 to 99,600), cancer (up 16,100 to 34,100), diabetes (up 14,800 to 46,900), asthma (up 11,600 to 44,900) and chronic kidney disease (up 10,600 to 35,600)..

- The overall number of health conditions is projected to rise 191,300 (54%) to 546,600 – with the biggest increase being seen in the number of people diagnosed with depression, which is set to more than double, affecting 164,200 people.

- The number of people with major illness will be seven times the increase in the working age population, impacting government income from taxes as people are unable to work.

- The key health issues facing children and young people will be mental health, obesity and child poverty.

What Liverpool can do

The report outlines a number of recommendations to address the challenges, including:

- Using data to embed a ‘health equity’ approach to making decisions. This will be assisted by £5 million of funding recently secured from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Determinants Research Collaboration.

- Working towards being a ‘Marmot City’ by April 2025, to address challenges in housing, income, climate change, mental health and welfare.

- Improving access to healthcare services for underserved communities to improve prevention and reduce health inequalities.

- Launching a new ‘Healthy Child’ programme in 2025, complementing the roll-out of five Family Hubs in the city, so that children young people and their families get the services they need to protect and develop their health and wellbeing.

- Integrating drug and alcohol services into a single, cohesive treatment and recovery service by 2025/26.

- Implementing a city region food strategy to improve access to healthy, affordable foods and eliminate food poverty.

- Improving the understanding of mental health and wellbeing and shape services with partners to increase prevention, early detection and support and recovery services.

What national government can do

The report makes three recommendations for government action:

- Devolved health powers to drive improvements in access to – and the quality of – services, plus the ability to set a minimum unit pricing for alcohol and introduce a fast food tax.

- National policy actions to tackle challenges such as child poverty, smoking, obesity and oral health.

- More investment in preventative services, including a 3-4 year funding settlement for local government to allow for longer-term planning and delivery of services.

Director of Public Health, Professor Matt Ashton, said:

“The findings are a stark and clear call for urgent action, not just by public bodies such as health services and the local authority, but for all those who have an interest in the current and future prosperity of the city.

“Poor physical and mental health shortens lives lived in good health and impacts not just on individuals but on those around them, such as other family members and the wider community.

“It is demonstrated to have a major detrimental impact on the economy through reduced productivity and increased demand for public services, and is a vicious cycle that needs to be broken.”

Liverpool City Council Leader, Cllr Liam Robinson, said:

“This report is a sobering read which lays bare the challenges we face in improving the health of our population.

“There are significant challenges linked to long-standing and endemic issues, particularly around poverty and poor housing. These have been exacerbated by cuts in welfare support and significant cuts to local authority spending which have impacted our ability to support our communities.

“We need to use this document as a catalyst to work together with our partners to implement the recommendations made within it, and to come together to lobby the government for devolved powers and long-term investment in services. Liverpool should have the ambitions of a devolved nation, for example I would argue that Liverpool needs the power to set minimum unit pricing on alcohol, which has had a positive impact on improving health outcomes in Scotland.

“From the appointment of Dr William Duncan as the first-ever Director of Public Health, to leading the way in making workplaces smoke free, Liverpool has a long and proud tradition of pioneering public health improvements – and this is exactly the moment when we need to do the same again.”

Cllr Carl Cashman, Leader of the Opposition at Liverpool City Council, said:

“This report needs to be read as a wakeup call for the city, the Council and the Government – that we need to take urgent action to improve health outcomes in Liverpool. It’s clear that there’s no quick fix, we need to take the lead together, as a local authority, to do what we can to improve the lives of our residents and eradicate health inequality in our city.

“As the opposition we will play our vital role in holding the administration to account and making sure they are delivering on the recommendations that Professor Ashton has put forward.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us