Culture

Slavery Remembrance Day is this month, but why is it so important in Liverpool?

7 years ago

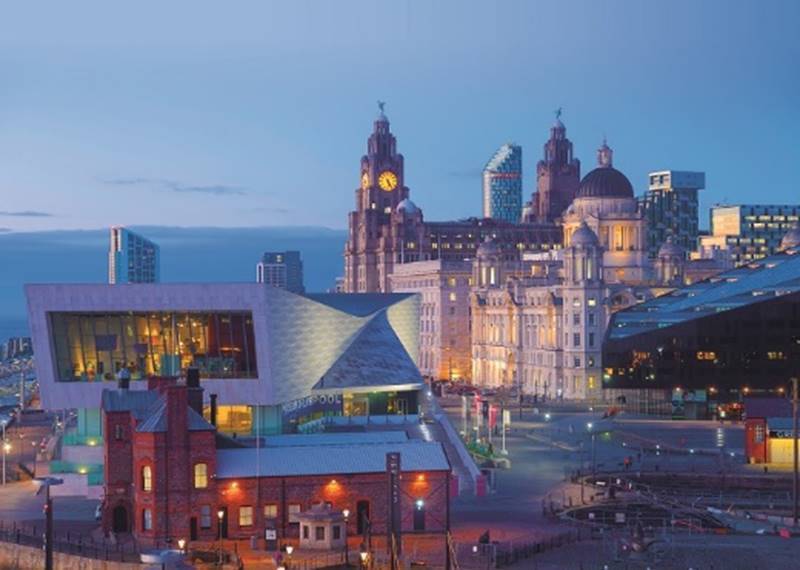

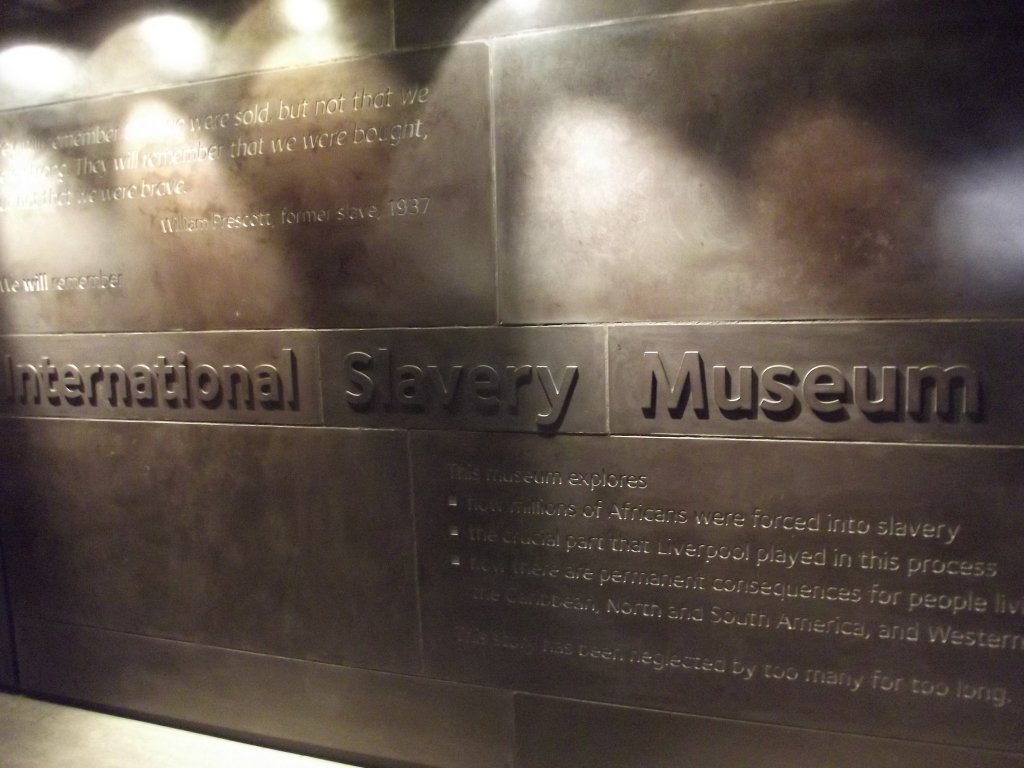

Liverpool will join a worldwide commemoration of Slavery Remembrance Day on August 23, with events centring around the International Slavery Museum at Royal Albert Dock.

The museum was opened on August 23, 2007 – coinciding not only with Slavery Remembrance Day but also the bicentenary of the abolition of the British slave trade.

So why is the day so important here and what are the city’s slave trade links?

In fact, Liverpool has more reasons than most to acknowledge the human cost of slavery as it once held the unenviable title of European capital of the transatlantic slave trade.

The slavery museum itself is located just yards away from the dry docks where 18th century slave trading ships were repaired and fitted out.

MORE: Get involved in this year’s Slavery Remembrance Day

80% of all British voyages in the final decade of the slave trade set sail from Liverpool, and the city transported an overall estimated 1.5million Africans across the Atlantic.

Despite not being involved in the trade in the early 1700s, when most British slavers ships left from Bristol and London, Liverpool became dominant within just a few decades.

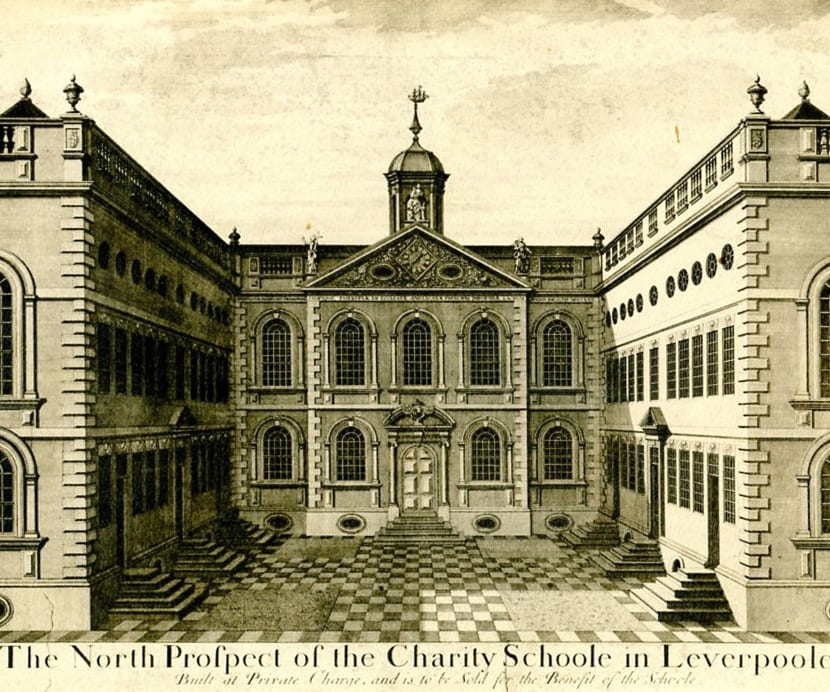

In 1725, when 400 ships left from Bristol and nearly 700 ships from London, 77 left from the Mersey – but by 1750 Liverpool was sending more slave ships than the other two cities combined.

Because so many local merchants and their ships were involved in slavery from the early 1700s until 1807, a large amount of the city’s wealth came from the slave trade. As well as the profits made by traders from selling slaves, slave ships were also often built or repaired in Liverpool, and the voyages were insured and financed by businesses based here.

Goods which were likely to appeal to African traders, like cloth and wool, guns and iron, alcohol and tobacco, were loaded on to the ships, ready to be used to buy slaves when they docked on the African coast. Liverpool’s links with Lancashire and Yorkshire meant it had a cheap, ready supply of textiles, it could easily bring in copper and brass from Staffordshire and Cheshire, and guns from Birmingham. Brandy from local distilleries was also popular for trading, along with rum imported from the West Indies.

Once the slaves had been bought in Africa, the next leg of the triangular trade then took them on to America or the West Indies where they were sold. Only a small number were brought back to Liverpool for sale at local auctions.

Conditions on the ships were horrific and slaves, who were fed on basic food like gruel, faced the constant threat of disease. A fifth of slaves died on the Atlantic crossing, and 40% of those who survived the journey died during their first year in captivity.

Although profits from each transportation weren’t always huge – it was very expensive to send out a ship (around £10,000 in 1790, which is well over £500,000 now) – sometimes they paid a massive dividend. One voyage to Africa, in 1780, by Mathew Street-based trader William Davenport’s ship made him a profit of £10,000 even after paying agents’ fees, the crew’s wages and other costs.

Most of the merchants involved in the slave trade were prominent figures in Liverpool, including many of its mayors – at least 25 mayors between 1700 and 1820 – and several of the city’s MPs invested in the trade and spoke in support of it in Parliament.

Being so potentially lucrative meant merchants didn’t give up their right to trade without a fight and even when abolition was proposed, 64 petitions of objection were submitted from Liverpool.

The Act of Abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade was finally passed in 1807 and the last British slave ship, the Kitty’s Amelia, left from Liverpool in July 1807.

On December 9, 1999 – 300 years after the first ship, the Liverpool Merchant, set sail – Liverpool City Council formally apologised for the city’s part in the slave trade.

MORE: School’s half marathon is launching in Merseyside

This will be the 20th year that Liverpool has taken part in the celebration, commemoration and remembrance of Slavery Remembrance Day.

Dr Richard Benjamin, Head of the International Slavery Museum, explained: “In uncertain and divisive times the legacies of transatlantic slavery, intolerance, racism, discrimination and hate crime thrive. That is why it has never been more important to support and get involved in Slavery Remembrance Day. In our 20th year, we’re inviting people to be active, to show their solidarity by walking.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us