UK News

Why are water bills going up so much, and how does it effect you?

2 years ago

Water bills are on the rise but why, and what does this mean for you as the consumer?

Household water bills in England and Wales are to rise by an average £19 a year over the next five years, under draft plans announced by regulators.

While the increase is a third less than water companies had asked for, it has sparked anger from consumer groups, after many firms’ dire records on sewage spills and water leaks.

Meanwhile, Environment Secretary Steve Reed promised steps towards “ending the crisis in the water sector”, including so-called customer panels to “hold (bosses) to account”.

What happens next and what it will mean for consumers:

What happened?

Every five years, England and Wales’ regional water suppliers must submit their business plans to regulator Ofwat for the upcoming half decade.

The plans include how far they can increase bills over the period and how much they will spend on upgrading drains, sewers and reservoirs.

Companies had asked for bill increases ranging from 13% over the five years to 73%. Thames Water, the country’s largest water company, asked for a 44% increase.

Ofwat published its initial draft ruling on the plans on Thursday. Most firms were told they would not be allowed to raise bills by as much as they asked.

The average rise proposed by Ofwat is 21%, about a third less than the average increase requested by companies.

What’s the damage?

Water firms wanted to raise bills by £144 on average over the next five years, but Ofwat has cut that.

For example, Thames Water planned a rise of £191 by 2030, but that has been reduced to £99.

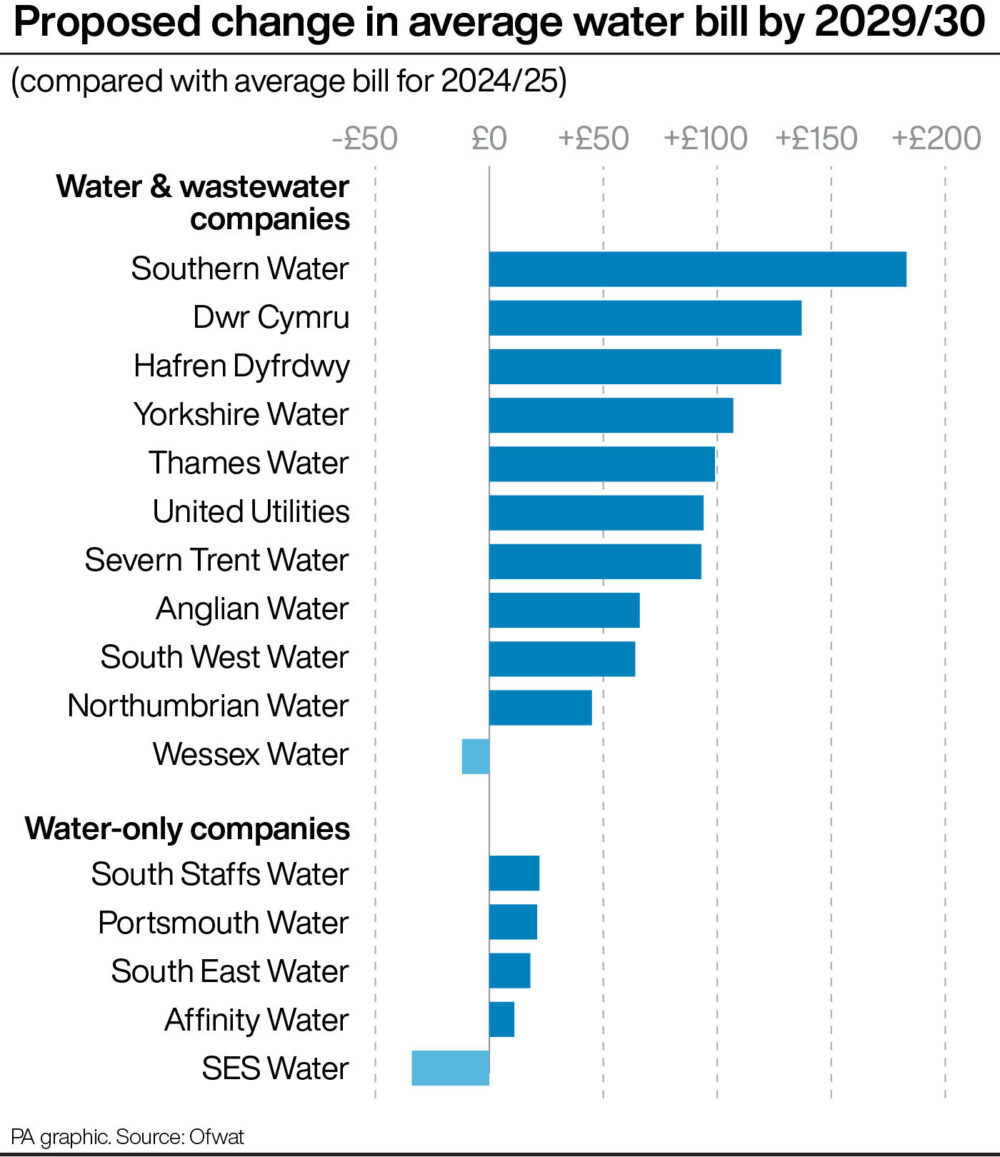

There are significant variations in price changes between firms.

Under the plans, Southern Water customers will face a £183 increase over five years, while Dwr Cymru customers’ bills will go up by £137.

At the other end of the scale, Affinity customers will see just an £11 rise, while SES customers’ bills will fall by £34 on the previous five years.

Why do they want to raise bills so much?

Water firms face serious problems with their drains, reservoirs and sewers, leading to vast amounts of pollution spilling into rivers and waterways.

That means firms need to spend billions on upgrading their systems, as well as turn a profit so they can keep getting more investment from shareholders.

To make matters worse, many face huge debt piles. The 10 biggest water companies have about £60 billion of combined debt.

Mike Keil, chief executive of the Consumer Council for Water (CCW), said: “Millions of people will feel upset and anxious at the prospect of these water bill rises and question the fairness of them given some water companies’ track record of failure and poor service.”

Why are people angry?

Critics say firms have chronically underinvested in their infrastructure since they were privatised in 1989, while paying out huge shareholder dividends.

In the 30 years since water firms moved into private hands, not a single major reservoir has been built in England and Wales.

Sarah Bentley, Thames Water’s previous chief executive, admitted before she resigned that it had been “hollowed out” by “decades of underinvestment”.

New rules were introduced last year to ensure that water companies do not pay dividends unless they are judged to have delivered for customers and the environment.

Mr Keil continued: “Trust in water companies has never been lower and that won’t change until people see and experience a difference, whether that’s having the confidence to swim at their favourite beach or receiving help if they are struggling to pay their bill.”

Is anyone trying to fix it?

Chancellor Rachel Reeves said the Government will “get a grip” on the sector.

Mr Reed said he would meet representatives from all 16 water companies from across England and Wales on Thursday.

He said he has written to Ofwat to ask them to make sure funding for vital infrastructure investment is ringfenced and can only be spent on upgrades benefiting customers and the environment.

He also said that consumers will gain “new powers to hold water company bosses to account” through so-called customer panels.

He said: “This unacceptable destruction of our waterways should never have been allowed, but change has now begun so it can never happen again.”

What happens next?

Ofwat’s ruling is only a draft decision, and begins a period of negotiation until its final verdict in December.

But the regulator has rarely made major deviations from its draft and final rulings in previous years.

That means Thursday’s statement gives all parties a rough indication of what the final decision on bills will look like.

If companies still do not accept Ofwat’s final ruling in December, they can appeal to the Competition and Markets Authority.

Ofwat chief executive David Black said: “Let me be very clear to water companies, we will be closely scrutinising the delivery of their plans and will hold them to account to deliver real improvements to the environment and for customers and on their investment programmes.”

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us