At Home

All the info on the new full-fibre cable offering that’s worth up to £1bn to Liverpool City Region

4 years ago

It’s just 18mm wide and made of tiny glass fibres, yet this insignificant looking cable promises to transform our lives and our economy.

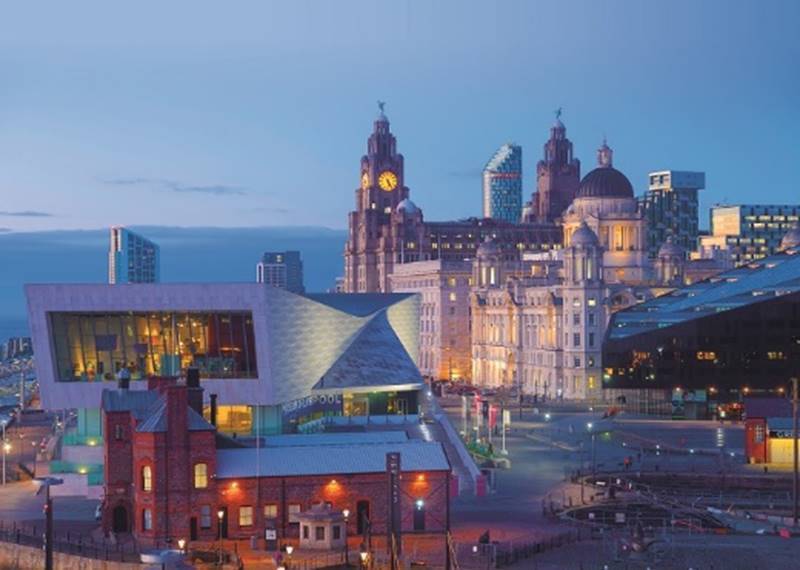

Being laid across 212km of the Liverpool City Region by LCR Connect, a 50% publicly owned joint venture, the ultrafast full-fibre cable will offer internet speeds of up to 100 gigabits per second (Gbps).

To put that in context, speeds of just 1 Gbps make it possible to download an hour-long HDTV show in nine seconds, consigning waiting for the spinning wheel of doom to the digital dustbin.

Work is underway across the Liverpool City Region to lay the fibre-optic infrastructure that is aimed at business customers and will generate an initial £105m for the local economy.

Experts estimate that, with 100% full fibre coverage across the city region, the economic boost could be worth up to £1bn, creating thousands of local job and training opportunities.

When complete, it will put city region businesses in prime position to lead the way in a host of growing sectors, from health and life sciences to Artificial Intelligence and advanced manufacturing. It could also potentially transform public services, including transport and health services.

But what is the cable made of and how fast is ultrafast?

- Fibre-optic cable allows us to have unlimited information at our fingertips and to send it around the globe almost instantly

- It’s made of glass strands. The cabling is used to transfer information via pulses of light

- It is surrounded in cladding to protect it – known as the buffer tube – and has an outer casing to make sure the glass fibres are fully protected

- The largest cable used on LCR Connect project contains 288 individual fibres, which makes an overall diameter of around 18mm (see pic attached)

- The individual fibres are 250 microns, about twice the thickness of a human hair

- The light that travels along the cable is on a part of the electromagnetic spectrum not visible to the human eye. NEVER look down a fibre cable to check.

- The cables are joined together by a machine called a fusion splicer. The two ends of the glass are heated to around 1800°C which melts them together effectively forming one continuous piece of glass.

- Although only tiny, the fibres have a surprisingly high tensile strength.

- Connectivity speeds are measured in bits per second. The bigger the number of bits per second your connection is capable of, the faster it can send information. The maximum capacity is known as bandwidth.

- In terms of speed, one gigabit per second (Gbps) is equal to 1,000 megabits (Mbps). At 10Mbps it takes around 15 mins to download an hour-long HDTV episode. At 30Mbps it takes 4.5 minutes however with a 1Gbps service, one episode could be downloaded in 9 seconds, or 100 episodes in 15 mins.

- LCR Connect will offer reliable ultrafast connectivity, with speeds ranging up to 100Gbps depending on the service chosen.

- That means downloading and uploading big files will take seconds rather than minutes

The cable is being laid by LCR Connect, a £30m joint venture, 50%-owned by the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, led by Metro Mayor Steve Rotheram, in partnership with North West-based ITS Technology Group, who will lead the project, working with construction partner NGE, who are managing the build and roll out of the network.

Alongside existing local digital infrastructure, the new fibre-optic network will help position the city region as a world leader in digital technology.

In its initial phase, the consortium is creating a resilient fibre ‘backhaul network’, connecting three transatlantic cables and major economic clusters in each of the Liverpool City Region’s six local authority areas.

Cable laying work has already started across all six boroughs of the city region.

Over the next two years, the 212km network will be installed beneath carriageways, footpaths and cycle ways across the city region, using innovative ‘dig once’ techniques to minimise the impact on road and public transport users wherever possible.

Existing ducts will be reused where possible to avoid disruption.

The network is not intended to deliver immediate benefits to residential consumers but a successful roll-out could be expected to attract new operators offering a greater variety of services at potentially more competitive prices in the future.

Subscribe

Subscribe Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us Follow Us

Follow Us